With their longships and pillaging, the inhabitants of the Iron Islands are clearly intended to evoke the Scandinavian peoples of the Viking Age (c.800-c.1100).1 Raiding, conquering, and terrorizing the seas of Martin’s world, the Ironborn strongly evoke the popular image of the Vikings. While some love this insertion, others are not so pleased by it. Martin draws heavily from history for inspiration for his series and by comparing his portrayal of the Ironborn to what we know of the Viking Age, one can determine which elements of the Iron Islands and its inhabitants are similar to those of Scandinavia and the Vikings and which elements are different. Aspects one should explore are the religion, social values, and treatment of women in Ironborn and Viking Age Scandinavian society; within these, one can find a variety of differences and similarities between the Ironborn and Scandinavians. What this indicates is that while many see the Ironborn as a parallel for the Viking Age, they are really more of a reflection of the popular image of the Vikings.

Dualism, Polytheism, and Creation: The Faith of the Drowned God and Viking Religion

When discussing the relationship between the Iron Islands and the Viking Age, a good place to begin is their respective faiths as their faiths set them apart from their contemporaries. In A World of Ice and Fire, Archmaester Haereg argues that “The ironborn… stand apart, with customs, beliefs, and ways of governance quite unlike those common elsewhere… All these differences… are rooted in religion”.2 Drawing on accounts from the late eighth to mid ninth centuries, The Annals of Ulster record similar religious differences when referring to Viking raids in Ireland; places such as Iona are “burned by the heathens”, places such as Etar are “plundered by the heathens”, and these “heathens” are also recorded to have “inflicted a slaughter in battle over the Déis Tuaisceirt”, among other things.3 These passages demonstrate that to the people of Westeros and Europe both put emphasis on the religious differences between themselves and their aggressors. As such, it is worth comparing these faiths to determine what remains consistent between them.

For the Iron Islanders, existence began when the Drowned God created them. From a passage in A Clash of Kings, one can observe that they were created “to reave and rape, to carve out kingdoms and write their names in fire and blood and song”.4 Believing themselves to have been born from the sea by the Drowned God, the Ironborn claim to be of a different race than the rest of mankind, one destined to rule.5 They shun the Gods of all other faiths, acknowledging only their Drowned God and his nemesis, the Storm God.6 According to their faith, “For a thousand thousand years sea and sky [have] been at war”, and upon death they go to the “watery halls” of the Drowned God.7 They also practice a ritual similar to baptism wherein the recipient of the ritual is drowned; sometimes it is a symbolic drowning, while other times the drowning is real, as is demonstrated in A Feast For Crows when Aeron Greyjoy preforms the ritual on a young man, concluding it with the common Ironborn prayer “What is dead may never die”.8

Theon Greyjoy Abandons the Starks and is ‘Drowned’

Drowned Priests such as Aeron Greyjoy are extremely important in the Faith of the Drowned God. Firstly, this is because their faith does not have temples or idols, making the Drowned Priests an important conduit to the Drowned God.9 In addition, it was Galon, a Drowned Priest, who first united the scattered kingdoms of the Iron Islands by ordering the first kingsmoot.10 These priests continued to influence the crown, with those they supported keeping their power and those they condemned losing it. This status quo continued until Urron Redhand slaughtered the kingsmoot held to depose him.11 Although previously broken, the power of the Drowned Priests has again arisen in Martin’s series, with Aeron Greyjoy calling the first kingsmoot in centuries.12

As previously mentioned, the Ironborn wholly reject the Gods of other faiths. During the reign of House Hoare, which ruled during the arrival of the Andals in Westeros, the Hoare Kings who tolerated the Faith of the Seven were despised.13 This friction led to violent uprisings led by the Drowned Priests; even after Aegon the Conqueror imposed the Faith of the Seven on the Ironborn, they managed to again have the Septons and their Septs banished from the Iron Islands.14

With this knowledge, one can observe that the Faith of the Drowned God is dualistic in nature, with the dead going to an afterlife to join their God. Lacking physical idols, the importance of the Drowned Priests is amplified. They also have a practice similar to that of Christian baptism, albeit more extreme, and their saying “What is dead may never die” indicates a harsh, fatalistic nature in their beliefs. Lastly, their rejection of other faiths meant that the presence of the Faith of the Seven in the Iron Islands was enough to cause unrest. Having considered these aspects of the Ironborn religion, one can move to examine the Norse Pagan religion for similarities and differences.

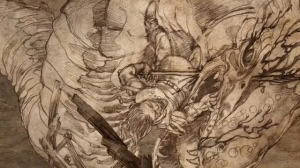

According to Snorri Sturluson’s account of the Norse Pagan creation myth, the first being to exist was the Allfather. After making the worlds beyond that of humanity, he created the frost giant Ymir, from whom the rest of the frost giants of the Norse Pagan faith would be born (all of whom were evil).15 Ymir’s cow, Authumla, then licked the salty ice from stones until a deity named Buri emerged, who begat three sons: Odin, Vili, and Ve.16 They killed Ymir, used his body to create the Earth, and created the first two humans, Ash and Elm.17 Also included in this myth are the Norns, deities who “shape the course of men’s lives”.18 From what we know of the Norse Pagan faith, the Gods would continue to exist and actively participate in conflict with the Giants until their final battle, Ragnorok.19 In this, one can see both parallels and differences with the faith of the Ironborn. Buri’s emergence from the salty rime is reminiscent of the salty sea-origins of the Ironborn, but is not really paralleled by it. While the Ironborn are dualist in nature, the Vikings were clearly polytheist. However, the conflict between the Drowned God and the Storm God is evocative of the Gods-Giants conflict of the Norse Pagans. Unlike the Norse Pagans, the Ironborn do not demonstrate a strong belief in true fate. Unlike the Ironborn, Scandinavian faith does not place them as automatically superior to all other humans. With these differences and similarities discussed, one can move on to discuss the reaction of the Norse Pagans to foreign religion and the material culture of their faiths.

While the Ironborn do not have objects or buildings associated with their faith, this was not the case for Norse Pagans. In his History of the Archbishops of Hamburg-Bremen, Adam of Bremen described a temple at Upssala; he describes the temple as being “entirely decked out in gold”, with people worshipping “the statues of three gods… the mightiest of them, Thor”, with Wotan (Odin) and Frikko represented by the other two statues.20 A Scandinavian saga also supports the existence of such temples, describing one being built by settlers in Iceland; this temple included “a bowl for sacrificial blood” on an alter, indicating that sacrifice was perhaps a common part of their faith.21 As the Ironborn do not practice ritual sacrifice as a common part of their religion, this is another difference between the faiths. The presence of the statues indicates that there was a material culture associated with the Norse Pagan faith that is not present in the Faith of the Drowned God, which emphasizes its holy men to a far greater degree.

Norse Pagan animal and human sacrifice, as depicted in the History Channel’s Vikings. Violence and gore warning.

In terms of accepting foreign religion, Norse Pagans were not as militant as the Ironborn were in their rejection of the Faith of the Seven. In his collection of sagas called the Heimskringla, Snorri Sturluson discusses the Christianization of Norway during the reign of Olaf II; those who did not convert to Christianity were, killed, “had their hands or feet cut off, or their eyes put out”, among other punishments.22 Sturluson describes the Pagans as trying to debate and reason with the King in order to continue on with their faith, only to be harshly punished and/or killed.23 Unlike the dualist Ironborn, the polytheistic Norse Pagans did not respond violently to outside religion, partly because their faith was inherently more accepting of new deities.24 An interesting parallel about conversion can, however, be made by again examining Adam of Bremen’s works. In his History, he discusses the conversion of Harald Bluetooth and the Danes and attributes Harald’s conversion to a defeat by Holy Roman Emperor Otto II, writing that as well as converting, he “promised to receive Christianity into Denmark”.25 After the defeat of House Hoare at the hands of Aegon the Conqueror, Lord Paramount Vickon Greyjoy agreed to allow the Faith of the Seven into the Iron Islands, evoking Harald’s conversion.26

These comparisons tell us a great deal about the relationship between the religion of the Iron Islands as it appears in A Song of Ice and Fire and Game of Thrones and the religion of Viking Age Scandinavians. The dualist religion of the Ironborn, although sharing similarities in conflict between deities with the Norse Pagan faith, caused a wholesale rejection of foreign faiths that Scandinavians did not participate in. In their rejection of material symbols and religious structures, the Ironborn rely on their Drowned Priests to connect them with their God. Ignoring gods of fertility and wisdom, Martin evokes only the most warlike aspects of his perception of Viking religion to create a cold, hard religion for a cold, hard people rather than a complex, multifaceted faith as developed organically for the Norse Pagans.

A Listing of the Norse Pantheon and their roles.

Traders, Raiders, Things, and Moots: The Traditions of the Iron Islands and the Vikings

First and foremost, the Ironborn are raiders. While the fishermen who provide food for the islands are considered to be respectable, it is the “reavers” who are given the highest praise in the Iron Islands.27 Sailing in packs of longships like Vikings, the reavers would plunder villages and towns before sailing away with loot and prisoners.28 Because of this tradition, the Ironborn before the Conquest often did very little trading with the other peoples, and those who did trade were looked down upon.29 While Vikings were, of course, infamous for their raids, they were also prolific traders. In the early 10th century, a Muslim diplomat named Ibn Fadlan encountered a group of Viking merchants along the Volga river; he describes them as selling “beautiful girls… and so many pelts of sable” as well as being pleased with cash payments.30 Because of their emphasis on violence and raiding, the Ironborn would consider such behaviour shameful, as is demonstrated when Balon Greyjoy lambasts his son, Theon, for being outfitted “like a whore” in jewelry paid for rather than reaved.31 In this rejection of trade, one can see a clear difference between the Ironborn and the Vikings, supporting the idea that Martin draws more from the violent popular image of the Vikings than from the reality of their culture.

Theon Greyjoy returns to Pyke only to be met with derision, even from his father (3:55).

As the means of transportation for the Ironborn and the Vikings, the longship is a clear parallel between the two cultures. The Vikings used a variety of types of longships that varied in size, but all such ships were capable of making war; their mastery of these ships meant that early Vikings could project power almost anywhere that had a coast or substantial river system, allowing them to raid and trade all across Europe.32 However, while the Vikings frequently targeted monasteries due to their accumulated wealth and poor defences, there is no indication that the Ironborn placed any such focus on septs.33 Against the land-lubbing First Men, Ironborn longships were extremely effective and gave them unmatched control of the sea.34 After the unification of the Iron Islands but before the arrival of the Andals, the Ironborn began to establish colonies on the mainland; the numerous kings of the Riverlands were forced to pay tribute, and coastal areas along the Western coast of Westeros were occupied.35 This conquest and settlement is evocative of the ninth century occupations of the Great Heathen Army, which occupied areas in Scotland, England, and Ireland in the late ninth century.36 After the Andals arrived and began to fortify the coasts as well as challenge Ironborn naval superiority, it became far more difficult for the Ironborn to reave “the green-land kings”; they had to go further abroad to raid, similar to how the improvement of coastal fortifications and increased organization under rulers such as Alfred of Wessex allowed for resistance to the Vikings.37 Furthermore, the Ironborn conquest of the Riverlands to form the Kingdom of the Isles and Rivers is evocative of Cnut’s North Sea Empire, although it was far longer lived (lasting until Aegon’s conquest, rather than until the death of its first ruler, Harwyn Hardhand).38 In these ways, the Iron Islanders do appear to draw a great deal from actual Vikings in terms of the history of their reaving, although they abandon the notion of trade.

Another comparison that should be made is between the kingsmoots of the Iron Islands and the Scandinavian things. In Viking Age Scandinavia, things were assemblies held for religious rites and to arrange for defence, as well as functioning as judicial and legislative assemblies; most were attended by representatives, but others, such as the Norwegian Eyrathing, were open to every freeman.39 In a manner similar to this, any Ironborn who captains a ship is able to participate in a kingsmoot, casting a vote towards who they wish to reign.40 The key difference here is that the kingsmoot does not serve as a judicial or legislative body, only as a kingmaking one. However, elements of the kingsmoot do evoke Viking themes; candidates at Aeron Greyjoy’s kingsmoot such as Erik, Victarion Greyjoy, and Drumm all present gifts of gold and plunder to the assembled captains in a manner similar to the gift-giving tradition commonly associated with Viking warbands.41 Besides these evocations, another interesting parallel comes out of Martin’s kingsmoot; in A Feast For Crows, one of the prospective kings says he will sail the Ironborn to a new paradise over the Sunset Sea.42 The Vinland Sagas describe several voyages taken by Scandinavians to North America around the year 1000, including Leif Erikson’s discovery of “Helluland”, “Markland”, and “Vinland”, now known to be locations in North America.43

Game of Thrones Academy predicts the discovery of “Americatos” or “Americassos”

Slavery and how different societies deal with it is a repeated theme in Westeros and Essos. In Scandinavian cultures, slaves had few rights; damages done to slaves meant payments to their owner, but slaves could also be recompensed smaller amounts for damages and were allowed to own some property. If a slave’s master acknowledged that the slave’s child was his, that child would not be a slave and was given equal status to any child born of the master and a freeborn concubine, similar to the practice of salt wives among the Ironborn.44 Like the Vikings, the Ironborn practice a form of slavery, calling it thralldom; thralls, once taken, would be put to work in fields such as mining or agriculture that were not respectable for Ironborn to participate in.45 However, unlike Viking slavery, “thralls cannot be bought or sold. They may own property… have children… [and] the children of thralls are born free”.46 By examining Scandinavian sources, one can determine both similarities and differences in these practices. The Laxdaela Saga describes a man named Hoskuld who goes to the market and barters to buy a slave for a cash payment of silver.47 The Heimskringla describes how a lord named Erling treated his slaves, writing that he put them to work in the fields but let them grow personal crops as well and helped them “get on in life” by letting them buy their freedom.48 What these show is that for the Viking Age Scandinavians, slavery was intertwined with economics; in contrast to this, the Ironborn didn’t even allow the trade of slaves. Ironborn thralls evidently enjoy a great deal more freedom than Scandinavian slaves did, but if Martin drew the basis for Ironborn thralldom from examples such as Erling’s treatment of his slaves, one can see that the two are not entirely dissimilar in terms of the liberties of the slaves/thralls, despite the running theme of trade being shameful.

George R.R. Martin discusses Theon Greyjoy and the practice of Wards/Hostages, a method used against the Greyjoys to secure peace from their warlike culture.

Through their raiding, conquest, slavery, and settlement, the Ironborn share a great many parallels with the activities of the Vikings during the Viking Age. As the First Men and the Andals became more militarily capable, the reavers were forced to look elsewhere for plunder, just as coastal fortification and political centralization were able to help defend against Viking raids. Alongside these similarities, the kingsmoot and potential to sail west are evocative of the Scandinavian things and the Norse discovery of North America. However, the dislike of trade present in Ironborn society is a distinct break from Viking practices. While the history and politics of the Iron Islands is more similar to that of Viking Age Scandinavia and the Vikings than its religion is, Martin can still be seen to be drawing on the more popular violent image of the Vikings rather than their true nature as both raiders and traders.

Women: Warriors and Wives

Although probably not historically accurate, the idea of the “shield maiden” is one commonly associated with Viking Age Scandinavia.49 The story of Hervor is one such story; in it, a maiden named Hervor decides that she wants to live a warrior’s life and puts down the sewing needle for the sword as she goes out into the world to seek her father’s grave.50 Other women, such as Ragnar Lodbrok’s probably fictional wife Lagerda (or Lagertha), are also depicted as warriors, with Lagerda “[fighting] in the front among the bravest men with her hair loose over her shoulders”.51 Although such warrior women would have been exceptional (or fictional), they are clearly evoked in Martin’s world by Asha Greyjoy (Yara in the televesion series). In A Storm of Swords, Balon Greyjoy remarks that his daughter “has taken an axe for a lover” and when sending his longships to attack the North, he assigns her thirty ships to Theon’s eight.52 At the kingsmoot, Asha is even given a great deal of support to be the first reigning Queen of the Iron Islands, but is unable to overcome the bias against her as a woman.53 By being a skilled warrior and captain but being unable to reach positions of high leadership, Asha is strongly evocative of the warrior women of Viking Age Scandinavian lore.

Lagerda/Lagertha as portrayed in the History Channel’s Vikings.

In Iron Island society, men are able to take a primary wife, called a “rock wife”, as well as multiple “salt wives”; salt wives serve as status symbols, and although children produced by them are able to inherit, they are always behind the children of the rock wife in terms of succession.54 This practice evokes that of concubinage, as has previously been mentioned. Also important to compare is the legal right of representation for women; with Iceland serving as example, Icelandic women could not attend the Althing and Scandinavian women generally couldn’t represent themselves in court.55 This lack of representation is clearly not the case in Martin’s world, as Asha is not only able to represent herself at the kingsmoot, but place herself forward as valid candidate. Through warrior women and the practice of rock and salt wives, Martin’s world is clearly meant to be evocative of Viking practices and legends, although not entirely accurate.

Conclusions of Traders and Raiders

In A Song of Ice and Fire and A Game of Thrones, Martin presents a long and complicated history and society for his Ironborn. Elements such as warrior women, longships, settlement, and conquest appear to be directly evocative of Viking Age Scandinavia and the Vikings. Other elements, such as their religion and disdain for trade, draw more on the popular image of Vikings than the historical consensus. Overall, the relationship between the Iron Islands and The VikingAge is one of inspiration, evocation, and some parallel, moreso in themes and events rather than individual characters and ultimately leaning more towards popular image than accuracy.

Works Cited

1Angus A. Somervilla and R. Andrew McDonald, The Vikings and Their Age (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2013), 152.

2George R. R. Martin, Elio M. Garcia, Jr., and Linda Antonsson. The World of Ice & Fire: The Untold History of Westeros and the Game of Thrones (New York: Bantam Books, 2014), 175.

3S. MacArit and G. MacNiocaill, ed. and trans., “The Annals of Ulster,” in The Viking Age: A Reader, ed. Angus A. Somerville and R. Andrew Mcdonald (Toronto: University of Toronto Press), 236-237, 239.

4George R. R. Martin, A Clash of Kings (New York: Bantam Books, 2011), 169.

5Martin et al., 175.

6Ibid.

7George R.R. Martin, A Feast for Crows, 28.

8Ibid., A Feast for Crows, 23-25.

9Martin et al., 175.

10Ibid., 179.

11Ibid., 179-182.

12Martin, A Feast for Crows, 40.

13Martin et al., 184.

14Ibid., 184, 188.

15Anthony Faulkes, ed., “Edda. Gylfaginning,” in The Viking Age: A Reader, ed. Angus A. Somerville and R. Andrew Mcdonald (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010), 76-78

16Ibid., 78.

17Ibid., 79-80.

18Ibid., 83.

19Somerville and McDonald, The Vikings and Their Age, 60, 62.

20F.J. Tschan, ed. “History of the Archbishops of Hamburg-Bremen, with new introduction by Reuter,” in The Viking Age: A Reader, ed. Angus A. Somerville and R. Andrew Mcdonald (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010), 102.

21Einar Ol. Sveinsson and Matthias Pordarson, ed. “Eyrbyggja saga” in The Viking Age: A Reader, ed. Angus A. Somerville and R. Andrew Mcdonald (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010), 103-104.

22Bjarni Adalbjarnarson, ed., “Heimskringla,” in The Viking Age: A Reader, ed. Angus A. Somerville and R. Andrew Mcdonald (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010), 409.

23Ibid., 410-412.

24Somerville and McDonald, 62-63.

25Tschan, 399.

26Martin et al., 187.

27Ibid., 176.

28Ibid.

29Ibid., 177.

30Albert Cook, trans., “Ibn Fadlan’s Account of Scandinavian Merchants on the Volga in 922,” in The Viking Age: A Reader, ed. Angus A. Somerville and R. Andrew Mcdonald (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010), 316.

31Martin, A Clash of Kings, 184.

32Somerville and McDonald, 10-11.

33Ibid., 16.

34Martin et al., 177.

35Ibid., 180.

36Somerville and McDonald, 25-26.

37Martin et al., 185.

38Ibid., 186-187.

39Somerville and McDonald, 45-46.

40Martin et al., 179.

41Martin, A Feast for Crows, 386-389.

42Ibid., 385.

43Einar Ol. Sveinsson and Matthias Pordarson, 352, 354.

44Ruth Mazo Karras, “Concubinage and Slavery in the Viking Age.” Scandinavian Studies 62, no. 2 (1990), 149.

45Martin et al., 177.

46Ibid.

47Einar Ol. Sveinsson, ed. “Laxdaela Saga.” in The Viking Age: A Reader, ed. Angus A. Somerville and R. Andrew Mcdonald (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010), 39.

48Adalbjarnarson, 40.

49Carol J. Clover, “Maiden Warriors and Other Sons.” The Journal of English and Germanic Philology, 85, no. 1 (1986), 36.

50Ibid., 37.

51Oliver Elton, trans. “The Nine Books of the Danish History of Saxo Grammaticus” in The Viking Age: A Reader, ed. Angus A. Somerville and R. Andrew Mcdonald (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010), 24.

52Martin, A Clash of Kings, 183, 394-395.

53Martin, A Feast for Crows, 392-393.

54Martin et al., 178.

55Someville and McDonald, 42-43.

Bibliography

Adalbjarnarson, Bjarni, ed. “Heimskringla,” in The Viking Age: A Reader, ed. Angus A. Somerville and R. Andrew McDonald, 40, 409-416. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press, 2010.

Clover, J. Carol. “Maiden Warriors and Other Sons”. The Journal of English and Germanic Philology 85, no. 1 (1986): 35-49.

Cook, Albert S., trans. “Ibn Fadlan’s Account of Scandinavian Merchants on the Volga in 922,” in The Viking Age: A Reader, ed. Angus A. Somerville and R. Andrew McDonald, 235-240. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press, 2010.

Elton, Oliver, trans. “The Nine Books of the Danish History of Saxo Grammaticus,” in The Viking Age: A Reader, ed. Angus A. Somerville and R. Andrew McDonald, 136-137. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press, 2010.

Faulkes, Anthony, ed. “Edda. Gylfaginning,” in The Viking Age: A Reader, ed. Angus A. Somerville and R. Andrew McDonald, 76-85. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press, 2010.

FollowHouseTargaryen, “George R. R. Martin – Speaks About Theon Greyjoy – Watch A Game of Thrones Online Free,” YouTube video. June 12, 2013. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v51PBrQwd68

Game of Thrones Academy, “Iron islands vs Vikings: discovering a new world?,” YouTube video. March 5, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s4o1yFFbZYs.

GoTSeason2, “Game of Thrones: Theon Greyjoy returns to Pyke,” YouTube video. October 5, 2013. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MXGPgNp719k.

Habershaw, Auston. “Why Are There Vikings in This Book?” Auston Habershaw. October 6, 2011. Accessed April 3, 2015. https://aahabershaw.wordpress.com/2011/10/06/why-are-there-vikings-in-this-book/.

HBO, “Grey King.” Source; Game of Thrones Wiki. Contributor: Gonzalo84. http://gameofthrones.wikia.com/wiki/Grey_King?file=Grey_king.jpg. All rights owned by HBO, used under fair dealing in Canada for educational and research purposes with no profit.

HBO, “Iron_Islands.png.” Source: Game of Thrones Wiki, Contributor: Werthead, http://gameofthrones.wikia.com/wiki/Iron_Islands. All rights owned by HBO, used under fair dealing in Canada for educational and research purposes with no profit.

HBO, “Pyke.jpg”, Source: Game of Thrones Wiki, Contributor: Werthead, http://gameofthrones.wikia.com/wiki/File:Pyke.jpg/. All rights owned by HBO, used under fair dealing in Canada for educational and research purposes with no profit.

Karras, Ruth Mazo. “Concubinage and Slavery in the Viking Age.” Scandinavian Studies 62, no. 2 (1990): 141-162.

Marguitx, “Viking Women (Lagertha – Vikings History Channel 2013) Katheryn Winnick.” YouTube video. May 27, 2013. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AGr7wsgWAsc

Martin, George R. R. A Clash of Kings. New York, NY: Bantam Books, 2011.

Martin, George R. R. A Feast for Crows. New York, NY: Bantam Books, 2011.

Martin, George R. R., Elio M. Garcia, Jr., and Linda Antonsson. The World of Ice & Fire: The Untold History of Westeros and the Game of Thrones. New York, NY: Bantam Books, 2014.

MacArit, S and G. MacNiocaill, ed. and trans., “The Annals of Ulster”, in The Viking Age: A Reader, ed. Angus A. Somerville and R. Andrew Mcdonald, 235-240. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press, 2010.

Nineteen1900Hundred, “Theon’s Bapstism: ‘What is Dead May never Die’ [HD].” YouTube video. April 21, 2012. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kOAZYjTJ1Ms

Saudii Ciinema, “Vikings – Sacrifice Scene.” YouTube video. May 23, 2013. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YuhBDkIn_RM

Somerville, Angus A., and R. Andrew McDonald. The Vikings and Their Age. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2013.

Strossen, Randall J. “Hafthor Wins World’s Strongest Viking, Sets Sights on World’s Strongest Man.” Hafthor Wins World’s Strongest Viking, Sets Sights on World’s Strongest Man. 2015. Accessed April 6, 2015. http://ironmind.com/news/Hafthor-Wins-Worlds-Strongest-Viking-Sets-Sights-on-Worlds-Strongest-Man/.

Sveinsson, Einar Old, ed., and Matthias Pordarson, ed. “Eyrbyggja saga,” in The Viking Age: A Reader, ed. Angus A. Somerville and R. Andrew McDonald, 103-104, 350-354. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press, 2010.

Sveinsson, Einar Ol, ed. “Laxdaela saga,” in The Viking Age: A Reader, ed. Angus A. Somerville and R. Andrew McDonald, 38-40. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press, 2010.

Tschan, F.J., ed. “History of the Archbishops of Hamburg-Bremen, with new introduction by T. Reuter,” in The Viking Age: A Reader, ed. Angus A. Somerville and R. Andrew McDonald, 102-103, 398-400. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press, 2010.

Vikingskog, “The Norse Gods,” YouTube video. December 16, 2008. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-_mc7zqrnsY.

You must be logged in to post a comment.